Unleashing the Mind: Fundamentals

Exploring the Tools for Thought Universe - From Amplenote to Zettlr - a no-nonsense, in-depth analysis.

This post is part of a series of articles digging deep into the current landscape of Tools for Thought.

In the last article of this series, I introduced my idea of making a journey through the tool universe. I explained how I evaluate them and what is particularly important to me. But before we can take off together, it is crucial to lay down the foundations.

What is Personal Knowledge Management?

Personal Knowledge Management, often called PKM, is a framework or system for individuals to gather, organize, analyze, and share knowledge. This process can involve various strategies and tools that help individuals keep track of and use knowledge to increase their productivity and efficiency.

PKM is often seen in professional contexts, where it helps individuals improve their learning, decision-making, and collaboration skills. It's also relevant in a broader life context, such as managing personal information related to hobbies or other interests.

The precise structure and operation of PKM can vary significantly from person to person, depending on their preferences, needs, and available tools.

It can be as simple as a notebook where an individual jots exciting ideas and information or as complex as a multi-platform digital system where files, notes, links, and ideas are carefully organized and connected.

The History of Personal Knowledge Management

The term "Personal Knowledge Management" (PKM) emerged as a natural extension of the concept of Knowledge Management (KM), which was itself developed in the early 1990s within the business and management fields. Knowledge Management initially focused on how organizations could effectively manage and capitalize on the collective knowledge within their structures. As the digital age progressed, it became apparent that individuals also needed systems to manage the ever-increasing influx of information they encountered in their personal and professional lives.

PKM, therefore, evolved to address this need at the individual level, focusing on how people can gather, categorize, store, search, retrieve, and share knowledge. It emphasizes the individual’s role in managing knowledge and recognizes the importance of personal responsibility in learning and knowledge creation.

The exact origin of the term is difficult to pinpoint, as it likely evolved organically from discussions and writings on knowledge management and personal information management. However, it gained more formal recognition in the academic and professional literature in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Key figures in Knowledge Management, such as Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi, who wrote about creating knowledge in organizations, may have indirectly influenced the development of PKM concepts.

What are Tools for Thought?

"Tools for Thought" are software applications, platforms, or methodologies designed to enhance, support, or augment cognitive processes such as thinking, learning, and understanding. These tools help individuals manage, explore, and generate knowledge more effectively. They are particularly relevant in the information age, where the ability to handle vast amounts of data and information is crucial for knowledge workers. Here are some common types and examples:

Note-taking and Knowledge Management Tools: Apps like Evernote, Notion, or Roam Research allow users to capture, organize, and retrieve notes and information. They often include features for tagging, linking related ideas, and structuring information hierarchically or in a network.

Mind Mapping and Concept Mapping Software: Tools like MindMeister or Coggle help visually organize and structure thoughts and ideas. They are helpful for brainstorming, planning, and making connections between concepts.

Outlining Tools: These tools, like Dynalist or Workflowy, enable users to create structured lists and outlines, which help organize thoughts, writing, and project planning.

Digital Workspaces and Whiteboards: Platforms like Miro or Microsoft Whiteboard offer a virtual canvas where users can collaborate, brainstorm, and visualize ideas using text, drawings, and other multimedia elements.

Personal Wikis and Databases: Tools like TiddlyWiki or Obsidian create interconnected information databases. They are helpful for research, complex project management, and compiling extensive knowledge bases.

Flashcard and Spaced Repetition Software: Tools like Anki or Quizlet help memorize and learn through flashcards and utilize spaced repetition algorithms to optimize learning efficiency.

Data Visualization and Analysis Tools: For more advanced users, software like Tableau or Alteryx helps visualize data, uncover patterns, and derive insights.

AI and Machine Learning Tools: Emerging tools like ChatGPT or Claude leverage AI and machine learning to process and synthesize information, generate ideas, or write code.

Programming Languages and Environments: For those inclined towards programming, environments like Jupyter Notebooks or RStudio can be powerful tools for thought, especially for data analysis and scientific research.

Literature and Reference Management Software: Tools like Zotero or Mendeley help researchers manage, cite, and share academic literature and references.

Task and Project Management Tools: Applications like Trello, Asana, or Jira help organize, prioritize, and track tasks and projects.

Collaborative Online Forums: Platforms like Stack Overflow or GitHub can be used for collaborative problem-solving, code sharing, and gaining insights from a community of users.

The boundaries between the categories are becoming blurred as the tools increasingly combine functionalities from different areas.

The History of Tools for Thought

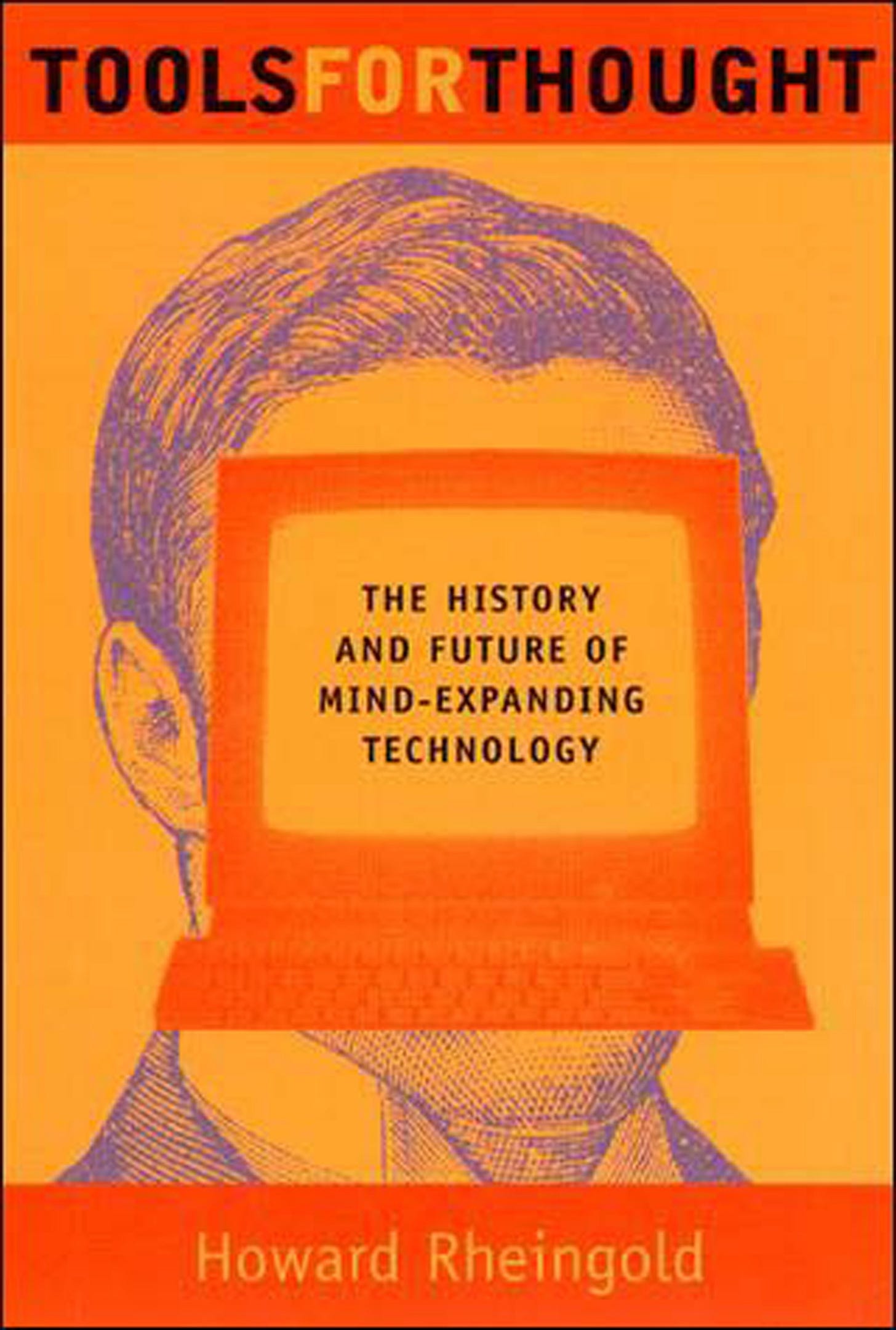

"Tools for Thought" is most prominently associated with Howard Rheingold and his influential book "Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology," published in 1985. In this book, Rheingold explored the evolution and potential of computers and digital technology as extensions and augmentations of human mental capacities.

Pioneers like Vannevar Bush, J.C.R. Licklider, Douglas Engelbart, and Alan Kay contributed foundational ideas that shaped this concept.

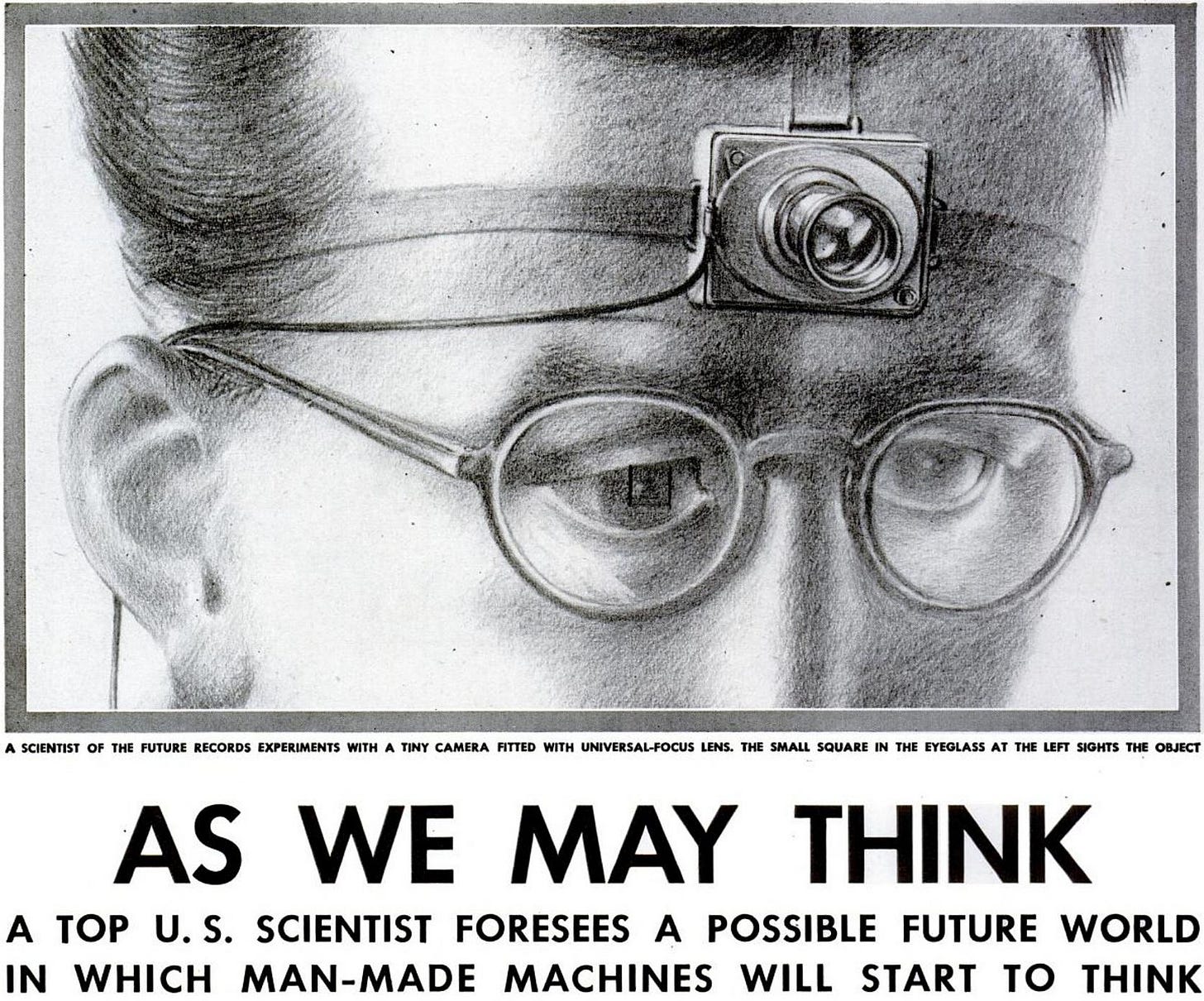

Vannevar Bush: In his 1945 essay "As We May Think," Bush envisioned the "Memex," a theoretical machine designed to help people store, categorize, and recall information. This idea was a precursor to hypertext and personal computing.

J.C.R. Licklider: Often credited with inventing the idea of human-computer symbiosis, Licklider foresaw a future where computers would become partners in solving complex problems and enhancing human thinking as well as decision-making processes.

Douglas Engelbart: Influenced by Bush and Licklider, Engelbart dedicated his career to developing technologies that augment human intellect. His work led to the invention of the computer mouse and the development of early graphical user interfaces.

Alan Kay: A pioneer in object-oriented programming and the development of graphical user interfaces, Kay was instrumental in developing concepts that underpin modern personal computing.

The term "Tools for Thought" thus encapsulates that technology - explicitly computing technology - can be designed and used to extend and enhance human thinking, memory, and learning processes.

The Core Process of PKM

Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) involves individuals' processes and strategies to manage their personal information and knowledge. While different people might have slightly differing approaches to PKM based on their needs, the core process usually includes the following elements:

Collection or Gathering: The first step involves gathering or collecting the information or knowledge you come across daily. This can include data from books, articles, blogs, podcasts, videos, online courses, personal experiences, or interactions. The aim here is to obtain valuable information from various resources.

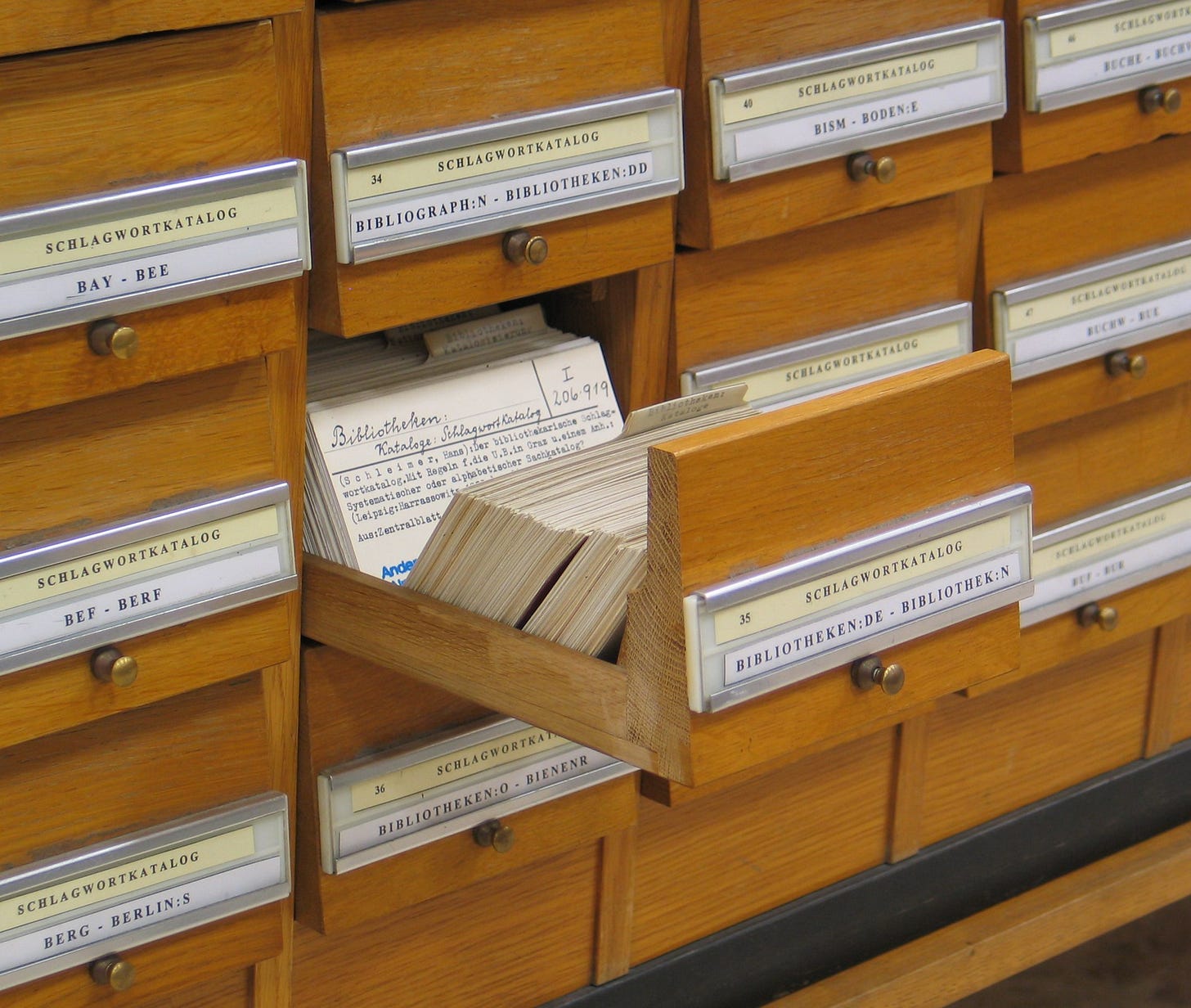

Organizing: The next step involves organizing the gathered information after the collection. This could be done in various ways, such as categorizing by themes, hierarchical structures, or using tags. The information can be stored in a physical system of files and folders or digitally using platforms like Notion, Evernote, Google Drive, etc. Organizing makes information retrieval easier in the future.

Analyzing: Once organized, the information must be synthesized and analyzed to understand its meaning, relevance, and context fully. This process involves thinking critically, identifying patterns, making connections, and integrating with existing knowledge.

Reflecting: Reflection is a critical part of the PKM process. It's when you take some time to think about the information you've been taking in, what it means, and how it fits into what you already know, as well as contemplating its potential applications and implications.

Sharing: Sharing is often an overlooked aspect of PKM but can be crucial. This can involve teaching others, writing blog posts, sharing on social media, or discussing with peers. Sharing information and knowledge can provide feedback, lead to deeper understanding and insights, and help others learn.

Updating: This is the continual process of revising your system, updating your knowledge, deleting irrelevant information, and adding new insights. As new knowledge is acquired, it is essential to update your PKM system to keep it current and relevant.

While these are listed as discrete steps, the PKM process is not linear and often involves revisiting and revising earlier stages. The process is personalized and may change with variations in an individual's methods, habits, or available tools. My upcoming reviews of the various tools will examine all these steps in depth.

Essential Aspects When Choosing a Tool

When choosing a "Tool for Thought," several vital aspects must be considered:

Usability and Interface: The tool should have an intuitive and user-friendly interface. A steep learning curve can be a significant barrier to regular use. The easier it is to navigate and input information, the more likely you will use it effectively. I already pointed this out in my introduction.

Customization and Flexibility: Different users have different needs and workflows. A good tool should be customizable to fit individual preferences and adaptable to various tasks and projects.

Integration with Other Tools: Considering how well the tool integrates with other applications and services is important. Seamless integration can significantly enhance productivity and ease information management.

Data Portability: The ability to export your data in a standard format is crucial. This ensures you can migrate your data to another tool if needed and safeguards against data lock-in.

Search and Retrieval Capabilities: Efficient search functionality is vital for quickly finding the necessary information. The tool should offer robust search capabilities, including tagging, filtering, and full-text search. Unfortunately, this cannot be taken for granted.

Data Security and Privacy: Understand how the tool handles your data, especially if it’s cloud-based. Consider the provider's privacy policy and security measures to protect your information.

Scalability: The tool should be able to handle an increasing amount of information and complexity over time. Consider how it performs under heavy loads and whether it can accommodate your growing needs. I did an investigation into this some time ago.

Support and Community: Access to support, whether through official channels or an active user community, can be invaluable, especially for complex tools. A strong community can also provide a wealth of resources and insights.

Cost: Evaluate the cost relative to the features offered. Some tools are free, while others require a subscription or one-time purchase. Consider your budget and whether the tool provides value for money.

Platform Availability: Consider which devices and operating systems the tool supports. If you use multiple devices or a less common OS, ensure the tool is compatible.

Offline Access: If you often work without internet access, consider whether the tool offers offline functionality.

Longevity and Developer Support: Consider the track record and stability of the company or developers behind the tool. Tools that are regularly updated and improved are more likely to be sustainable in the long term.

Selecting the right Tool for Thought depends on personal preferences, work habits, and your specific tasks. All these aspects will be considered in my journey through the Tools for Thought Universe - to boldly go where no man has…you get the rest.

We are taking off with the following article, in which we look at Amplenote in-depth.

See you soon!

Alex

Creating high-quality, insightful, and valuable content takes time, effort, and resources. To continue delivering content that meets these standards and to sustain the work involved in producing it, I have decided to make the upcoming articles of this series available exclusively to paying subscribers.

I encourage you to consider a paid subscription to support my work.